Miwa Sado Japanese journalist works herself to death: The culture of Karoshi, where workers are compelled by duty and responsibility- but at what price?

Miwa Sado a 31 year old TV reporter in Japan has died after literally working herself to death.

Local reports told of the journalist logging 159 hours of overtime and only taking two days off in the month before her death.

The workload equated to Sado having worked an average of 5.9 hours overtime a day including weekends — around twice the average contracted working week of 40 hours.

The Japan Times told of the 31 year old political reporter who worked for public broadcaster NHK in Tokyo dying of congestive heart failure in July, 2013.

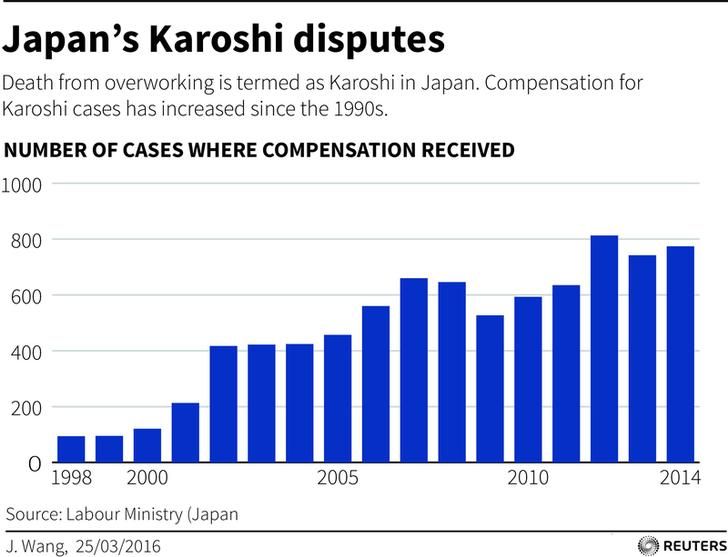

A local labor standards office attributed her death to karoshi — death from overwork – a year later, but her former employer only publicized her case this week.

Her death sheds light on the oppressive work culture in Japan, where employees who work very long hours have been dying in increasing numbers.

According to a national survey, a fifth of the country’s workforce are at risk of karoshi, since they clock more than 80 hours extra work time each month.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s administration has been trying to improve labor conditions after Matsuri Takahashi, 24, a new hire at ad agency Dentsu, committed suicide in 2015.

Officials ruled that her death was a result from stress induced by long work hours. She had amassed 100 hours of overtime a month.

In the weeks before her death, Takahashi had posted on social media, ‘I want to die.’

Added the woman, ‘I’m physically and mentally shattered.’

Responding to Sado’s death, her employer, NHK claims it kept tally of the reporter’s hours through personal statements and time cards. The outlet has since conceded there was room for improvement reported The Guardian.

Company official Masahiko Yamauchi said Sado’s case was a ‘problem for our organization as a whole, including the labor system and how elections are covered.’

Yamauchi said the case was kept under wraps for this long partly because of the wishes of Sado’s family.

Her relatives now say they want to make sure such a tragedy doesn’t happen again.

‘Even today, four years after, we cannot accept our daughter’s death as a reality,’ her parents said in a statement released by NHK. ‘We hope that the sorrow of the bereaved family will never be wasted.’

Japan’s government – which said one in five workers were at risk of death from overwork — proposes to cap monthly OT at 100 hours and to penalize companies that allow their workers to go over.

Of note, more than 2,000 people killed themselves in Japan due to work-related stress in the year to March 2016, while dozens of others died from heart attacks, strokes and other conditions related to their jobs.

Japanese employees work much longer hours than their counterparts in the US, Britain and other developed countries, according to research.

Miwa Sado Japanese reporter: The culture of Karoshi and how it sees no trend in abating.

Karoshi — or death from overwork reports the UK’s Sun has been blamed on a combination of Japanese workers’ commitment to duty and increased competition for jobs.

Karoshi became widely recognized as a phenomenon in the late 1980s, as stories of blue-collar employees keeling over at work appeared to expose a sinister side to Japan’s postwar economic miracle.

Over the years, cases of karoshi have been reported among white-collar executives, automotive engineers and immigrant trainees as they have taken on long hours, unpaid overtime — known as ‘service overtime’, along with shorter holidays becoming the norm.

‘In a Japanese workplace, overtime work is always there. It’s almost as if it is part of scheduled working hours,’ said Koji Morioka, an emeritus professor at Kansai University who is on a committee of experts advising the government on ways to combat karoshi. ‘It’s not forced by anyone, but workers feel it like it’s compulsory.’

The Japanese government released its first ever investigation into the karoshi crisis last year revealing staff at 12 per cent of corporations put in more than 100 hours of overtime every month.

Employees of a further 23 per cent of the nation’s companies were only slightly better off, working 80 hours of overtime each month.

Of the 10, 000 companies invited to participate in the survey only 1,743 across the nation invited to take part in the inquiry did so.

In February, the country launched a campaign urging workers to leave early at 3 p.m. on the last Friday of every month, the Independent reported. It isn’t clear if employees are necessarily heeding such calls as Japanese culture continues to exact standards of perfection and commitment.

Come May, more than 300 companies had been found to breach labor laws.