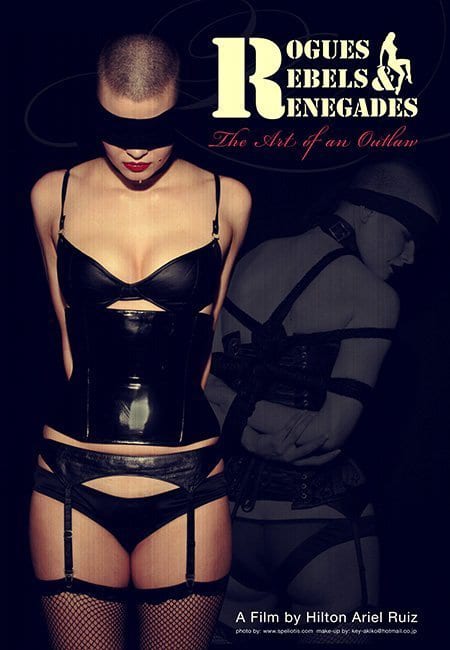

This past Tuesday afternoon I made my way to the Lower East Side to visit filmmaker Hilton Ruiz for a private screening and conversation about his as-of-yet unreleased documentary, Rogues, Rebels and Renegades: The Art of an Outlaw. Admittedly, I was a bit nervous about watching a documentary that explores pornography as art alone with Hilton, a mere acquaintance. My unease increased as I sat down in the same buttermilk yellow chair that the naked woman in red rope bondage reclined in during a particularly intimate scene in the film.

But this is the first purpose of Hilton’s documentary. That is, to make his audience uncomfortable. As a former photography gallery owner, Hilton was familiar with the NYC “art world” and its never ending conversations defining what is and what is not art. Not one for strict definitions, Hilton never weighed in on this debate. Not until a friend asked if he would feature a show on fetish photography at his gallery.

Be ware, he was warned by the status quo, if you hang these photos, your gallery will develop a certain kind of reputation and forever be associated with that world. Though Hilton never found an answer to what world, exactly, these voices ominously eluded to, it seems to me they were referring to the community of people interested in exploring the nature of human sexuality both inside and outside of the porn industry.

Most Americans are not particularly interested in openly exploring their sexuality. Sure, women might be willing to buy magazines that have ten tips on where to sprits perfume because that’s where “our man” likes to kiss. And there might be a Maxim magazine nestled in next to a Newsweek at the paper stand. But these public displays of sexuality are not a marker of our sexual openness, so much as one more aspect of our culture that we have sold off to advertising agencies for them to accessorize and sell back to us as neatly packaged sexual identities.

Defying this mass produced, pre-packaged sexuality is the second purpose of Hilton’s documentary. It is not an investigation into the history of sexuality in America or a political statement about free speech. Rather, it is a compilation of interviews with six artists featuring three men and three women, five of whom are photographers and one who is a cartoonist.

Each artist’s work is different from the next. There are drawings of naked sex-super-heroines using “pussy farts” to catapult into the sky, photographs of couples engaging in oral sex to add to their collection as well as the moment of a delicate kiss captured on a toilet between two women as one expels the hot wax enema used in their lovemaking ritual.

Cut in with these images are a string of conversations with the artists and the people in the photographs. As we listen to them, we quickly realize they are not the stereotypical “old, dirty men” we might imagine people who take photographs of sex to be. Rather, they are people compelled to express their interest in love and possessiveness, play and passion, by capturing other people’s physical pleasure with their lens. As one photographer explained, after years of working on S&M porn shoots, she wanted to take photographs of people whose everyday sex life was S&M. People for whom S&M was love.

Listening to this line, I began to relax in the buttermilk bondage chair. These people are not harming me, I thought. They are capturing people practicing what their erotic selves desire or sharing their body with another. Yes, I was watching a woman bottomless in a pink-netted shirt tongue a glass dildo while I sat next to a man who was practically a stranger. But no one was telling me to strip or asking me what kind of sex I like to have.

And that brings me to the third purpose of Hilton’s documentary, which is simply to give these artists a voice. When they speak, they do not demand that we all look at their work. They do not demand that we all start wearing more black leather or asking to be blindfolded in the bedroom. What they do ask is that we let them be.

As I listened to one woman explain how the ropes woven around her set her free from being self-conscious about her body, I got the sense that there was something incredibly healthy about these artists and their photography. They have taken rare images of people in the midst of pleasure, documenting what makes them feel good, in a society brimming with images of what sexy is supposed to be.

Some people might consider these images to be obscene or perverse. Perversity can be defined as rejecting what is “right and good”. But when it comes to our own bodies, the artists, Hilton included, ask for the right of each individual (I need to clarify that I exclude children and non-consenting adults) to accept, seek and explore their own “good.”

After the film rolled to an end, I swiveled in the infamous chair to face Hilton and begin my line of questioning. At times, I felt like a Supreme Court Justice trying to pressure him into locating the line that divides art from obscenity. These questions come from a place inside of me that longs for an all-encompassing and true morality. But in the end, I hope, Hilton’s tone of open acceptance comes through.

KH: How did you come up with the title?

HR: During the course of the interviews, I realized the artists feel like they are rogues, rebels and renegades. They are outlaws because they are artists not treated equal to other artists. And they are rebels because they do their art in spite of the fact that society does not accept it.

KH: Why is their art not accepted?

HR: The art world confuses it with work that is not artistic. And our government has the power to censor it.

KH: Can you give me an example of what the art world confuses it with?

HR: Well, when there is sex and photography involved, people jump to conclusions about sexually deviant behavior. They sometimes assume it will be like straight up boy/girl fuck films or a porn magazine.

KH: What about the work featured in your documentary is artistic?

HR: To me, these six specific artists are expressing themselves and doing what they love. That is artistic. Art is the result of an artist expressing how he feels and what he likes. Any form of expression can be art and everyone has his own way of feeling what art is.

KH: Where is the line between art and pornography?

HR: The line? Porn can be art. It’s a matter of how you look at it. It all depends on your definition or art and your definition of porn. And everyone has different definitions. This question is going to be debated forever.

KH: You seem to resist definitions!

HR: Well, yeah. It could go forever. It’s very hard to define. It’s more of a personal feeling than expressing it in words.

KH: You feel that the work in your documentary is art because the people doing it are expressing something. What they are expressing is explicitly sexual. Is it obscene?

HR: Child pornography is obscene. Outside of that, my own opinion is basically “to each their own.”

KH: Our government holds a different position. Even though the First Amendment guarantees us freedom of speech, speech that is deemed “obscene” is not protected. This is a little bit broader than just child pornography, as you say.

HR: Well, if you look at porn, you’re not going to think it is obscene. I think if you want to look at porn, go ahead. If you don’t, don’t. People are always going to have different opinions and tastes.

KH: How does our society influence our opinions and tastes when it comes to sex?

HR: I’m not going to comment on “society at large”. I think we are influenced by how we are brought up, mostly, and what we are directly exposed to. Being from NYC, I learned to flow with everybody. Because I grew up with different sexualities around, I accept them. When I interviewed the artists for this documentary, nothing shocked or surprised me. My objective was not to make a statement about sex or pornography, but to understand the individual I was interviewing.

KH: What is it that you understand about them now?

HR: I understand that they are struggling. I sensed their feelings of not being appreciated, of constantly being judged, by our society. But they are just taking photographs and drawing pictures. They’re not hurting anybody. And they’re more open-minded than a lot of people. Making this documentary (and showing their photography a few years back when I first had the idea for the documentary), I experienced some of this judgment. I had people call me and say, “you’re ruining your gallery. Now people are going to connect you to another world. A world that people don’t accept.” I would ask, “what world?” They never had an answer for me. I didn’t understand them. It’s just art.

KH: In the face of this judgment, why did you decide to go ahead with the gallery show and then the documentary?

HR: Because I appreciate the photography and understand being a struggling artist. For me, having a gallery that made room for all types of artists was very important. And this documentary has allowed me to continue making room for artists who normally are not given a voice.

KH: It seems a noble crusade. Were you ever nervous about stepping outside of what is accepted?

HR: Well, I think all artists get to a point where people do not always accept what they do. If people choose not to accept what I am doing, I still feel like I did something. Even if they do not approve of it or praise it, the least I did was make them more aware of what is out there.

KH: What are you saying by giving these artists an opportunity to speak?

HR: I’m challenging the audience to look and listen before they judge. And when the do judge, judge for themselves. Also, I think the work is interesting and I want to see this genre out there as art.

KH: You’re comments about these artists not being accepted reminds me of the question you continually raise in the documentary, “why does our society tolerate explicit violence on screen and not explicit sex?” Do you have an opinion on this matter?

HR: As Americans, we are born with violence in us. We accept violence from the beginning because we are a violent society, a violent country. Everything about our history is violent. This one book I read has this quote that says something like: the central American soul is a killer. Do I agree with it? To a certain extent. Sex, on the other hand, has never been accepted.

KH: Do you think perhaps we don’t accept sex because it gives us personal power?

HR: Of course. We are threatened by those who are more sexual. We get envious when someone can work the sexual element, the erotic.

KH: What do you mean by erotic?

HR: Eye opening in a sexual way.

KH: Some of the content in the documentary focuses on S&M and fetishes, for example bondage. Some people might look at a woman tied up in a rope with a blindfold on as violent. Can sex be violent?

HR: That’s a good question. To me, if it’s violent, it’s not sex. It might be rape. If two people consent to having forceful sex, that’s different. That’s not violence.

KH: What do you want a mass audience to take away from your documentary?

HR: First, don’t judge before you see it. These artists are members of our society. We should not abandon them because of the art they do. I hope those who see the documentary become more open-minded, open to this form of art and more sexually open with themselves.

KH: Why do you think being open-minded is so important?

HR: I’m not saying that everyone should be open-minded. If I did, it would defeat the purpose of me saying “to each their own.” This is my own.