Mark Langedijk Dutch man euthanasia: the moral dilemma of mercy killing a man with alcoholic addiction. Has the law gone too far and what risks exist?

In a move that has stoked disconcert, a 41 year old Dutch man, Mark Langedijk has been allowed to end his own life under Holland’s euthanasia laws after the self admitted drunk saw little hope of staying alive.

In an account published by his brother, Langedijk told of choosing death as the only way to escape his alcohol addiction.

Hours prior to his own impending death the man was observed joking, drinking beer along with eating ham and cheese sandwiches prior to the arrival of his GP at his parent’s home, where a fatal injection was administered.

Local reports note the death of Mark Langedijk marked a new departure in Dutch euthanasia practice, which killed more than 5000 people last year.

The scope of the mercy killing law, introduced 16 years ago to apply only to those in unbearable suffering, has already widened so that those who die include many whose problems include ‘social isolation and loneliness’.

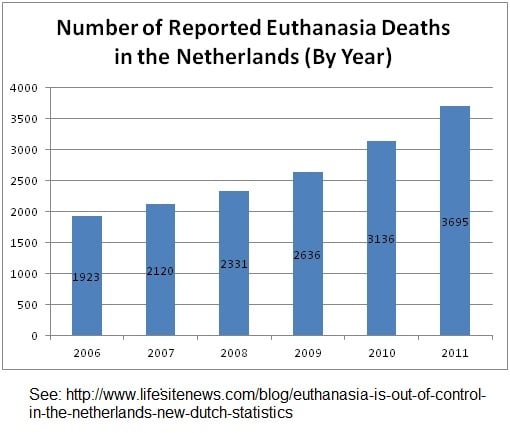

Based on the 2015 Dutch government statistics, the number of euthanasia deaths increased by 289% since 2006 with 5561 reported euthanasia deaths. Among those deaths there were 109 people who died by euthanasia based on dementia, up from 81 in 2014 and 56 people died by euthanasia based on psychiatric reasons in 2015, up from 41 in 2014.

A regard of the chart below shows the obvious: death by euthanasia in Holland is increasingly becoming a state sanctioned mandate, setting off the question at what point does a society deem a person’s state of being is no longer worth living and should any entity ever have the right to facilitate such notions?

Told Scott Fischbach, executive director of MCCL GO via lifenews in September: ‘Thousands of Dutch patients are intentionally killed by euthanasia or assisted suicide each year,’

‘Some are killed because they have dementia or psychiatric problems, like depression or post-traumatic stress. And some mentally incompetent patients are killed even though they have made no request to die.’

The plight of Mark Langedijk appeared in local Dutch magazine Linda, in which brother Marcel tells of how the two brothers and sister Angela had shared a quiet, easy-going and happy childhood in the eastern Dutch province of Overijssel, where they had been ‘carefree children.’

It was only about eight years ago the article mentions that the family discovered that Mark Langedijk had a drinking problem.

Told the addicted man’s brother: ‘Psychologists, psychiatrists, GPs and other health care professionals did their best to help him, but Mark could not explain to anyone what he felt,’

Adding: ‘I was particularly angry at Mark. At first we did what most people do: help,’

‘My parents especially have done everything humanly possible to save Mark. They adopted his two children, they took him in when his marriage finally collapsed, they helped him find accommodation, they arranged rehab, they gave him money, support and unconditional love.

‘Through eight grueling years and 21 hospital and rehab admissions they continued to believe in a happy ending.’

Nevertheless Marcel Langedijk said, his brother would only return to drinking again after every attempt at rehabilitation.

It was there that it was decided nothing could be done, and that the best solution would be for the afflicted sibling to die.

Recalls Marcel Langedijk: ‘We took it with a grain of salt,’

Adding: ‘Euthanasia was for people with cancer, people suffering unbearably, people for whom death was imminent. Euthanasia was certainly not for alcoholics.’

He said his brother told his GP: ‘I want to die, enough is enough.’

Diary entries were shown to the GP in which evidence was provided to show that life had become unbearable, with one passage reading, ‘a hopeless cocktail of pain, drink, loneliness and sorrow.’

Soon after, Mark Langedijk’s application for euthanasia was approved by a doctor from Support and Consultation on Euthasia in the Netherlands, the medical body set up to provide expertise on euthanasia.

It was there that the 14th of July, Mark Langedijk death by euthanasia was set, which was described by the afflicted brother as a ‘nice day to die’.

The man’s death reports the dailymail was noticed in the UK, with British MPs saying the euthanasia death of Mark Langedijk was evidence of the ‘slippery slope’ effect in which euthanasia, once legalized, can be spread to wider and wider groups of people.

Said Fiona Bruce, Tory MP for Congleton and co-chairman of the All Party Parliamentary Pro-Life Group: ‘This news is deeply concerning and yet another reason why assisted suicide and euthanasia must never be introduced into the UK.

‘What someone suffering from alcoholism needs is support and treatment to get better from their addiction – which can be provided – not to be euthanized.

‘It is once again a troubling sign of how legalized euthanasia undermines in other countries the treatment and help the most vulnerable should receive.’

Robert Flello, Labour MP for Stoke-on-Trent South, said: ‘Yet again Holland demonstrates it is a dangerous place to have any physical or mental illness, to be struggling with any life challenges, or just to differ from what they might call normal.

‘The state-authorized killing of their citizens is out of control and is, quite frankly, terrifying.’

Reflected the brother, Marcel Langedijk via the independent: ‘Alcoholism and depression are illnesses, just like cancer. People who suffer from it need a humane way out.

‘It’s not like we go around killing people in Holland. It took my brother a year and a half and many struggles to get it done.’

The death of Mark Langedijk has led to some wondering given the man’s addiction whether he was mentally competent to make the decision to choose to end his own life, while others decry the notion of any body having the capacity to legally end any person’s life beyond that of terminal illness, while others including this author wonder at what point does a society deem ‘what is terminal, to be done away with, discarded, too complicated to continue,’ when so often such illnesses are innately tied to one’s state of mind as opposed to necessarily physical being?