The chelfitsch Theater Company’s U.S. debut of 5 Days in March begins before the lights dim in the theater when two male hipsters meet center stage and begin speaking in Japanese. They tell us that they will be telling us a story. From these first lines, director Toshiki Okada let’s us know there will not be a fourth wall in the theater this evening because his play’s purpose is to put real life on stage.

Nor will there be traditional action fueling a plot that reveals a theme. The characters will not go through some kind of emotional transformation and there will be no lights down as the crew scurries through a scene change because there are practically no props.

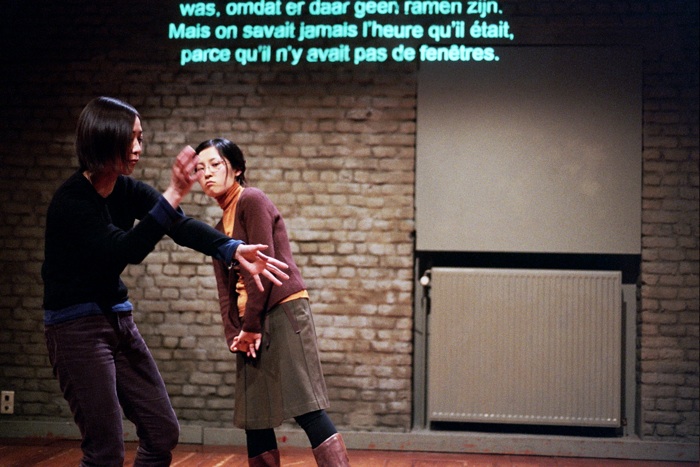

During the course of the play, man-made material reality never surrounds the actors, establishing an absence of visual context. This lack of stuff challenges the actors to use their brains, their voices and their bodies to fill up the blank space. They use only themselves to communicate as opposed to relying on things. So they carry their bodies, full of gestures, as though every…single…movement…they make is another way of expressing all of the things they want to say to us like what they’ve done and what they think.

In some ways their movement resembles puppetry. Sometimes they extend their arms and loosen up their legs so that they hang in the air as they speak. And when they are silent, they crumple to the side of the stage like a pile of painted wood and string. At other times, their bodies remind me of animals, specifically the sloth or some noisy primate. Though it does not really exist, I envision them hanging out together in a giant canopied tree where some groom each other and tell stories in their primate slang, while others lounge around listening casually.

The actors in 5 Days in March never pretend at living and climb a fake staircase or ask their date to pass the bowl of peanuts. None of these things go on because this play is not the kind of theater in which characters act. Instead, as the hipsters explained to us, they talk…and talk…and talk.

The story they tell goes something like this: Two guys went to a Canadian rock concert in Japan. One guy got left behind and missed his train after the other guy went off with a girl who was a stranger to have sex three dozen times in a love hotel near a familiar train stop. The strange girl is a Japanese girl who speaks English (so sexy) because she studied abroad in the U.S. where she lived with an American family. The sex stint started on the same day that the United States invaded Iraq in 2003 and continued as Japanese protestors, surrounded by police, marched towards the American embassy in their own battle for peace. The hipsters tell us that they are sitting in a breakfast place as they recount this story.

Sex. War. Breakfast. These things are pretty commonplace. And, at first, I feel like I am a pedestrian engaging in a random eavesdropping session on a subway train. Not an audience member, just a person listening to all of the people chatter about cafes they have never been to, errands they need to run, bad movies they’ve seen or what happened at the bar after you passed out. This perpetual jabber, the kind that fills up the blank spaces of everyday life, is the language of the play.

But is takes on a new significance when portrayed on the empty stage for us to watch. By emphasizing the everyday act of recounting a story, Mr. Okada is telling us to forget about time and place and take a moment to listen up. In doing so, he gives us the opportunity to be silent and listening, a practice that has all but gone extinct in modern, industrialized society. Amidst all of the babble, we hear Japan’s “generation Y” engage in an act of public contemplation about violence, commitment and purpose. We are confronted by man’s struggle to tame his inner beast. We are asked to question the consequences of commitment to things like ideology and economic systems.

In the end, we are not simply eaves dropping for an hour and a half on Mr. Okada’s perspective. We are engaging in a communal reflection on America’s war in Iraq, globalization’s impact on culture and the ironic and impotent state of the modern human condition. And though this story does make me feel sad or angry or tired, this method of theater does not leave room for us to feel sorry for ourselves. Rather, it engages our intellect and implores our rational, conscious selves to think about how we are currently choosing to exist. Because. It. Is. Our. Choice.

I sat down with the Japan Society Theater’s creative director, Yoko Shioya to discuss the chelfitsch Theater Company, their production of 5 Days in March and why she chose to present it to an American audience.

It is difficult to ask or answer questions about a play whose characters refuse to say any one thing too strongly. Every time I attempted to turn the play’s subject matter into a statement filled with meaning, Yoko challenged me to not hold to one perspective. But while I struggled with allowing the play to exist like mercury, fluid and ungraspable, Yoko seemed to conclude one thing about the subject matter of the play. He conclusion seems to be that my generation, 20 and early 30 somethings, in the US and Japan have no idea what we think and, therefore, are not sure of who we are. Nor do we seem to want the responsibility of making that choice. What ensued was an attempt at communicating about communication and how the way we communicate reflects who we are.

KH: What is unique about chelfitsch Theater Companies’ production of 5 Days in March?

YS: The dialogue in the play is perhaps its most unique element. It is a new way of playing with language. Toshiki Okada, the writer and director, has broken away from linear dialogue to express time in a more casual manner.

KH: Why did Mr. Okada do this?

YS: Because it shows the way that young people, in their 20’s and early 30’s, speak in Japan today. It is a way of speaking that lacks a reference to time and certainty. You cannot tell if the events in the play occurred in the past or are happening in the present.

KH: The past and the present are blurred in the play?

YS: Not exactly blurred. I need a strap. Do you have a strap?

KH: Will a belt do?

YS: Yes a belt.

Adam, my press contact for the interview who was sitting in on the beginning of the conversation, removed his belt and handed it over to Yoko. She turned it into a large loop with one twist so that the outside of the belt turned into the inside of the belt in an endless loop. Tracing her index finger around the outside until it followed the path and moved to the inside ring, she explained,

YS: You see it is not simply a blurring of time, so much as there being no difference between past and present at all. You cannot blur the edge of time if there is no edge there to begin with. It is all one. This is the Japanese language. It is not like English. It is not mathematical or scientific. There is no tense. The events in time are in relationship with each other, they go and come and come and go.

KH: Why does Mr. Okada emphasize the seamless-ness of time in the language of his play?

YS: First, it is the nature of the Japanese language. But, this generation has exaggerated it. Mr. Okada did not invent this manner of speaking. It exists in the younger generation of Japanese society today. He has simply put it on stage.

KH: What do you mean exaggerated it?

YS: The younger generation speaks without commitment and responsibility. When they say something, they blur what they think with what other people think. They do not take a stand on their own or show commitment to their opinion.

Holding up a piece of paper, Yoko says in a bold voice, puffing out her chest,

“I think this is great.” When I say, “I think this is great,” I am saying that I am okay with conveying to others that I think this is great. But the way the younger generation speaks, they do not offer such strong convictions. They say, “Well, it’s kind of like, I kind of like it, as others say.” Are they saying what they think or are they just repeating what others say? I have no idea what is true for them because their use of language avoids facts, commitments and responsibilities.

KH: What are the consequences of this generation’s use of language to speak without offering their own perspective?

YS: I think it makes it difficult for them to enter into mainstream society. They bounce around from part time job to part time job and never stick to one thing long enough to get a promotion or advance in their career. But the job market in Japan is partly at fault for this. The economic situation has made it difficult for young people to get a job and be in a business environment, which would help them refine their ability to communicate. In a way, the younger generation is stuck in a post-college, pre-work apathy. Historically in Japan, people have worked for one company from the time they graduate from college until they retire. This was a rule. But about ten years ago the economy burst and this rule no longer worked, resulting in a “lost decade.” The lost generation has a lack of confidence in themselves because they have not been given the opportunity to grow and achieve.

KH: How does this economic situation impact this generation’s psychology?

YS: It makes them always feel vulnerable and as though they exist on the margins of society. This is why they speak the way they do, without certainty. It is a defensive state of psychology.

KH: Yoko, I love speaking with you. But I think you will hate my review! I thought the play’s use of exaggerating chatter said something. And isn’t it significant that the 5-day love affair between the couple begins on the same day that the US invades Iraq and in the midst of peace protests in Japan?

YS: The play discusses two people having sex for five consecutive days. It discusses the Iraq war. It discusses the protests. And people complaining about the protests. There are all of these different parts happening at the same time. You cannot judge one scene based on the other scene because the play does not exist in this way. You cannot define the shape of the production because it is a moving thing. It might sound like I am trying to avoid explaining or analyzing the whole thing, but the play is not science and analysis always leaves something behind. This play has an organic movement of its own that you have to see in order to feel.

KH: Speaking of movement, why does Mr. Okada have the performers move with odd, repetitive gestures?

YS: Think about what you might do if you are sitting on the couch with your friends. You might move in a way that is totally unrelated to what you are speaking about. Mr. Okada’s choreography emulates the unconscious gestures of our natural life. As opposed to traditional theater’s use of movement to help convey emotion, he is depicting what we do naturally. In real life, we do not put our hand to our forehead and toss our hair back when we receive startling news. We do things like fidget, shake, squirm and stretch. Mr. Okada’s emphasis on this is not really odd; it is a kind of hyper-naturalism.

KH: What is the message Mr. Okada is trying to send by putting our realistic movements and use of language up on stage?

YS: It is not a message. It already exists. He is just putting the different sides of our reality onto the stage so that we can become aware of what we already are dealing with on a daily basis.

To further explain Mr. Okada’s intention, Yoko picks up a cup and says,

YS: If you look at the cup from straight on, it is the shape of a rectangle. But if look at the cup from underneath, it is a circle. Both of these things are true at the same time. Mr. Okada’s play shows us the circular side of the cup. A side that exists, but that we are not aware of. Art should do this.

KH: How has Japan received this art?

YS: Some consider it a kind of masterpiece in our society. This kind of non-committal language has been a sort of social problem in Japan. The ministry of education tries to figure out how to maintain the “good, correct and proper” language, which has been in danger from this younger generation’s way of speaking. But in this play, Mr. Okada has taken this way of speaking and turned it into the main engine of a very interesting piece of theater.

KH: For someone who pays such close attention to language, I assume that chelfitsch means something significant?

YS: It is the way an infant would mispronounce the English word “selfish.” This is Mr. Okada’s understanding of the young generation in Japan. We expect children to mispronounce words, but when adults do it, it is wrong. He is commenting on society’s creation of a generation that has not matured to adulthood.

KH: Why did he choose the word “selfish”?

YS: It reflects this generation. Children are supposed to be self-centered. They don’t know how else to be. But a grown up should know what selfish is and that it is not good to be too selfish. We now have a generation that looks, physically, like they are adults, but that does not even understand the word “selfish” enough to pronounce it correctly.

KH: If the play is about Japanese youth culture, why have you chosen to show it to an American audience?

YS: Even though the play’s grammatical structure is different, the same mentality exists in the younger generation of Americans. They don’t get to the point. It irritates me when younger people speak so that the end of their sentences go up, like they are asking a question. “I like the chicken. So I went to the restaurant. And I think that boy is sort of cute” (ken, rant, cute are all delivered in a higher pitch). Are you saying something, or are you asking me a question? I don’t know if you like the chicken or if you went to that restaurant or if you think that boy is cute. Do you know?

KH: Do we?

Coming up next at the Japan Society presents Awaji Puppet Theater Company.

Check out: http://www.japansociety.org/ for more details.

This reminds me of the Taylor Mali spoken word piece “Speak With Conviction” where he discusses uncertainty in our language. Invisible question marks, ya knows, likes, etc.

Holy Mama…….! Talk about serving up a discussion on abstract socio-economic symbolism by way of eastern mind set cloaked in Shintoism! You just made Oregami out of both sides of my brain and somehow, strangely I now know, I won’t be having much erections for the whole month to come…

The fact is, the Japanese, having survived the A-bomb treatment, have by leaps and bounds advanced their thinking way beyond our staid, ego centric, consumptive self gratificational, cultural orientation. So yes, they probably are the one society that could lead the world in some advanced socio thinking… I was convinced of that way back at the height of Godzila genre in the Seventies…and of course, no wonder that they can… They are stressed environmentaly and in population extremes… There’s not much room to exercise indulgence or excess. Yes, we ought to listen up and learn, but this for us is heavy and being Americans is not how we roll…