In the midst of Armory Week’s champagne cocktails and pretentious (albeit enthralling) parties, it was refreshing to attend a powerful opening where the focus was, shockingly enough, the art. Curated by the perceptive Jan Van Woensel and his curatorial assistant Vanessa Albury, UN-SCR-1325, an exhibition that investigates the state of women in various sociopolitical contexts, opened last Thursday at the Chelsea Art Museum.

The show was named for the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 which, for those of you who don’t keep a mental catalogue of UN activity, was “the first resolution passed by the Security Council that addresses the impact of war and conflict on women, as well as conflict resolution and sustainable peace efforts.”

Now don’t be fooled by preexisting notions and arty stereotypes; the exhibition is no feminist pity party or tired political war against our abomination of a 43rd President. Rather, it’s an exploration of the “resilient reactions of women to negligence, discrimination and intolerance.” It provides a window into the physical and emotional state of women in crisis and questions what, if anything, the future holds.

Originating at Belgium’s Geukens & De Vil Gallery, the first UN-SCR-1325, curated by Yasmine Geukens and Marie-Paule De Vil, combined the works of 8 female Belgian artists. In his rendition of the show, Van Woensel added the works of 8 American artists to create an exhibition that is both emotive and relevant.

“It is important for people to look at the relationship between the artworks. The real message is not in one piece, but in the dialogue between all the pieces,” explained Van Woensel as he gave me a proud tour of the exhibition.

Many of the works utilize literal language as a way to question the current feminine state. Jen DeNike’s circle of ethereal photographs depict the artist standing in a starry, snow-covered atmosphere, using flag signals to spell “What do you believe in.” Surreal and angelic, the work is hopeful and encourages us to believe in something grandiose.

Marlene McCarty, an artist who has made her mark with drawings of abused and damaged teens (e.g. Patty Columbo), contributed a pen-drawn triptych of gorillas speaking in sign language. Each panel depicts raw sketches of two furry friends signing, “hug,” “stink,” “sorry,” and “baby.” The sweet primal beasts question our origins and seem to ask, “How can we think beyond violence?”

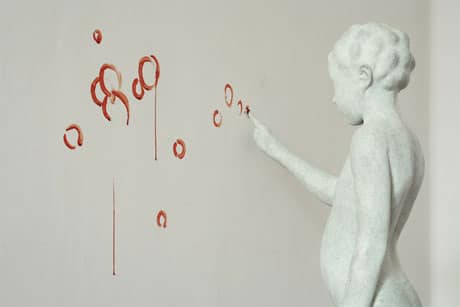

Not all the works, however, were so encouraging. With its materials listed as “bronze and blood,” Sofie Muller’s Eve was unsettling, to say the least.

A stark white sculpture of an androgynous child, the figure is drained of life except in its crusted, flesh-toned feet. Eerily elegant, the child reaches toward the wall to draw clusters of dripping circles with the artist’s blood.

Dealing with space and isolation, Eve evokes a jarring reaction; it combines a delicate sadness with a horrifying view into the depths of mental disruption caused by abuse and trauma. Innocence is gone, only numbed pain remains.

Berlinde De Bruyckere’s Marthe conveys an equally dark message. A frail headless figure sculpted in wax, Marthe is pulled to the ground by the grotesque roots that grow from her shoulders. Unable to escape from social and self-inflicted pressures, the strangely beautiful creature hunches in agony as she succumbs to unbearable suffering.

However it was Adrian Piper’s Everything #4 that truly embodied the spirit of the show. Inscribed in gold leaf on a Snow White-esque mirror is the phrase, “Everything will be taken away.”

Piper’s ominous work can only be understood when one looks at more than just the foreboding statement. Self-reflection is a clear component. But we must also examine our relationship to the text, to the reflections of our surroundings, to the reflections of the people around us. The mirror forces us to confront the larger picture, the relationships between.

A profound and seamlessly edited exhibition, UN-SCR-1325 illuminates a very real problem. It is a delicate balance of positive and negative, doom and hope, reality and dream. It challenges us to consider the uncomfortable space between, the overwhelming truths. Will everything be taken away? Perhaps if we look a bit harder in the mirror, or maybe even outside of it, we’ll find out.